It was early summer when I began to feel stuck in my work. A presentation in London had ended in failure, and a quiet urge had started growing in me—perhaps it was time to reconsider my career path. That’s when a friend living in Tokyo messaged me: “Why not visit Naoshima?” A curious little island, she said, where art lives in harmony with nature.

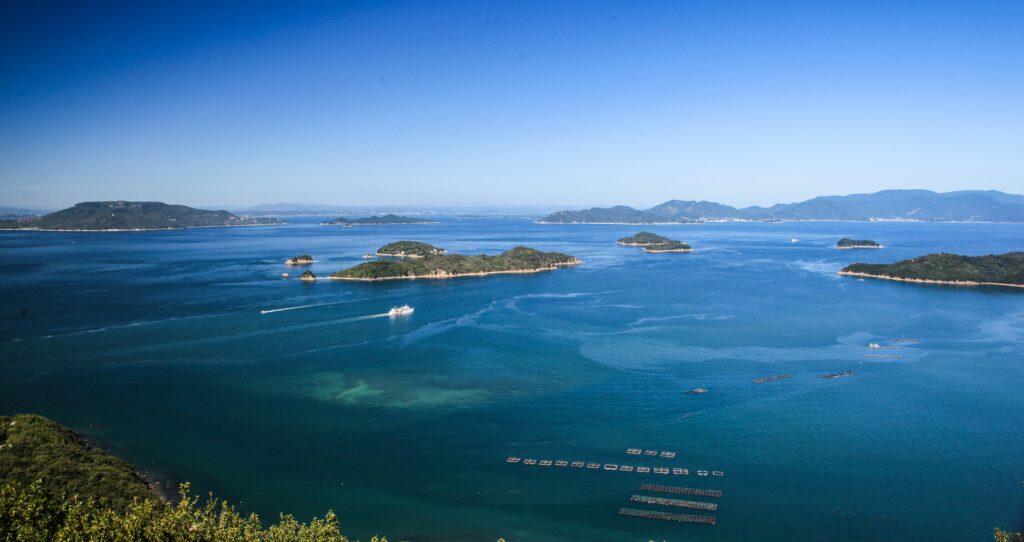

Naoshima is a small island in the Seto Inland Sea, off the western coast of Japan, in Kagawa Prefecture. On the map, it looked like a tiny jewel gently placed on the water. Kagawa, located in northern Shikoku, is one of Japan’s smaller prefectures and is famously known as “Udon Prefecture.” From Takamatsu Airport, I took a train and then a ferry, letting the journey slow me down as I made my way to the island.

When I arrived at the port, a soft breeze brushed my skin—early summer had just begun. The sky stretched high above, and the clouds drifted slowly. My first stop was the Chichu Art Museum, most of which is buried underground, just as its name—“chichu,” meaning “in the earth”—suggests. The artworks, illuminated solely by natural light, seemed to breathe. Designed by Tadao Ando, the museum opened in 2004 as part of a regional revitalization project. The story goes that a passionate entrepreneur and the local community wanted to bring new life to the island through art.

Stepping into James Turrell’s “Open Field,” I felt the boundaries between myself and the world dissolve. I’d spent years surrounded by numbers and deadlines, but perhaps this was what it truly meant “to see.”

For lunch, I wandered into a small udon shop tucked away in a back street of the island. The wooden building was simple, with a noren curtain swaying in the wind. Inside, the air was filled with white steam and the scent of dashi broth. The handmade Sanuki udon noodles were firm yet silky, and paired with cold broth, grated ginger, and chopped scallions—it was a perfect balance. I hadn’t felt hungry before, but I couldn’t stop eating.

That evening, while walking near the port, I was approached by a young man who also appeared to be traveling solo. He was slightly younger than me, from Belgium, with a slender build, dressed in a white cotton shirt and linen trousers. He spoke soft English in a European accent. It was his second visit to Japan, this time focused on contemporary art. He said he was deeply moved by the Chichu Art Museum, “It feels like the building itself is a work of art,” he said, eyes bright. “It’s quiet, but it stirs something deep inside,” I replied, and he nodded with a gentle smile. Despite our different backgrounds, we connected instantly. It was a brief conversation, but one that reflected the quiet power of the island.

Later that night, on my way back to my lodging, I felt something shift inside me. The trees swaying in the sea breeze, the sun tilting slowly toward the horizon, and the island’s quiet voice, like a memory whispered from afar—each of these touched a part of me I hadn’t noticed in a while.

The next morning, I returned to the mainland and visited Ritsurin Garden, located in the center of Takamatsu. Built in the Edo period, it’s a former feudal lord’s garden. In the soft morning light, the scene looked like a living Japanese painting—pine trees reflected in the pond, the gentle curves of landscaped hills caressing the air. Even the voices of tourists seemed hushed, as though the space itself was designed for those who cherish silence.

For the final part of my trip, I traveled to Shodoshima, a larger island southeast of Naoshima. Once a hub of maritime trade, it is now known as the “Olive Island.” It was here, in 1908, that Japan’s first successful olive cultivation began. With a climate resembling the Mediterranean, the island has since been colored by the silvery-green of olive leaves.

I climbed a hill slightly inland to reach the Olive Park. A white windmill and rows of olive trees gave the place a faintly foreign air—like the Mediterranean had somehow merged with the light and sea of Japan. The breeze carried a hint of salt, and the afternoon sun lit up each leaf as if to reveal its own story.

At a café nearby, I ordered an olive oil ice cream—smooth and softly green. Its gentle sweetness carried a subtle bitterness, like an unripe fruit. I was surprised by its delicate balance: creamy yet refreshing, somehow nostalgic. It felt as if the entire journey had been distilled into that one flavor.

Unlike the bustling metropolises of Tokyo or Kyoto, these islands of the Seto Inland Sea possess a quiet beauty that defies description. More than a place to “sightsee,” it felt like a place simply to be.

What I discovered on this journey wasn’t anything grand or dramatic. It was the kind of beauty that simply stands there—like the scent of leaves swaying under early summer sunlight, a stranger’s kind words carried on the sea breeze, or the slow melting of ice cream in the palm of your hand. Modest, unassuming—and yet, it gently touches the heart.

It reminded me how precious it is to step away from the rush to achieve or to define meaning, and instead to simply let the wind carry you across the water, to narrow your eyes in the warmth of the sun, to receive the scenery and the people in front of you, just as they are.

Art, early summer, the sea, the wind, the sun, and the stillness of nature—together, they opened something soft within me. It wasn’t about understanding. It was about feeling. The days I spent on Naoshima gave me back that awareness—something quietly irreplaceable.

Naoshima, Kagawa