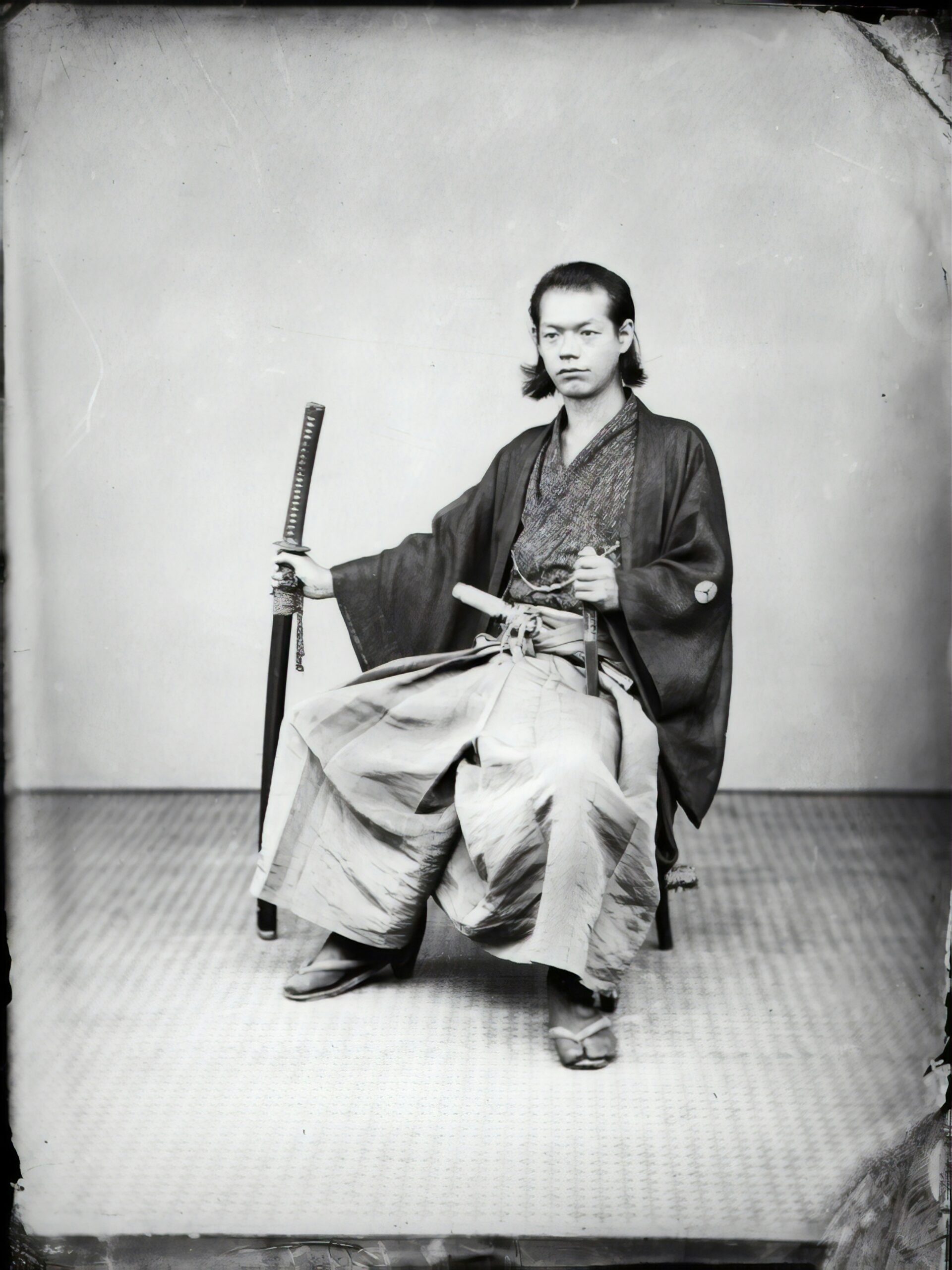

When journeying through the Japanese landscape, one often steps into the profound stillness of an ancient temple or the formidable shadows of a feudal castle. Yet, for the discerning traveler, these are more than mere architectural relics. They are the physical manifestations of an intellectual legacy that has anchored the nation for over 800 years: the spirit of the Bushi, or as they are more globally known, the Samurai.

Who were these men, and why does their philosophy continue to resonate so deeply across the modern world? To understand Japan, one must peel back the layers of this warrior-aristocracy.

I. The Dual Identity: “Bushi” vs. “Samurai”

In the Western historical imagination, the warrior is often cast as an instrument of force. In Japan, however, this class evolved early on into a sophisticated governing elite. The distinction lies in the subtle nuances of their titles:

- Bushi (The Warrior): Originating around the 10th century, this term refers to those born of the martial tradition. It evokes the raw excellence of the bow and the sword, rooted in the pride of lineage and personal valor.

- Samurai (The Retainer): Derived from the verb saburau (“to serve by one’s side”), this title speaks to a more refined duty. As the centuries progressed, these warriors transformed from mere soldiers into “literary and martial” polymaths—intellectuals who administered the law, performed sacred rites, and curated the arts.

The preserved residences of Kanazawa or the castle towns of Hagi do not radiate ostentatious wealth. Instead, they whisper of “restraint” and “dignity”—a philosophy where status was validated not by luxury, but by the cultivation of the self.

II. Echoes of History: A Global Context

The ascension and transformation of the Samurai occurred in tandem with the Great Waves of global history, grounding their unique development in a familiar timeline.

| Era | Key Characteristics | Global Context |

| Kamakura & Muromachi (1185 – 1573) | The Rise of the Warrior & Zen Military rule begins; a culture of rugged simplicity and Zen Buddhism takes root. | The Crusades and the dawn of the Renaissance in Europe; the expansion of the Mongol Empire in China. |

| Sengoku & Azuchi-Momoyama (1573 – 1603) | Unification & Golden Aesthetics Tactical evolution meets a peak in castle architecture and the Way of Tea. | The Age of Discovery; the Elizabethan Golden Age; the life of Leonardo da Vinci. |

| Edo Period (1603 – 1868) | 250 Years of Peace Under isolation, the Samurai evolve into a scholarly bureaucratic class. | The Industrial Revolution; the American Declaration of Independence; the French Revolution. |

While much of the world was embroiled in the turbulence of the 18th and 19th centuries, Japan’s “Great Peace” allowed the Samurai to sublimate their martial energy into a moral and aesthetic code.

III. Anatomy of the Spirit: The Triad of Zen, Confucianism, and Shinto

The Samurai’s worldview was a hybrid philosophy, harmonizing three distinct spiritual pillars into a practical guide for living.

1. Zen: Minimalism as Mastery

Living in the constant shadow of death, the Samurai sought mental equilibrium through Zazen (meditation). The Zen principle of “stripping away the unnecessary to grasp the truth” birthed the minimalist beauty of the Japanese Tea Ceremony and the Karesansui (Dry Landscape Garden).

2. Confucianism: The Architecture of Order

During the peaceful Edo era, the Samurai turned to Confucianism to define “Justice” (Gi) and “Etiquette” (Rei). Their honor became synonymous with social responsibility and unwavering loyalty—not just to a person, but to a moral order.

3. Shinto: Reverence for the Sacred Earth

Japan’s indigenous faith instilled a sense of “purity.” This is visible in the sacred rituals of sword-smithing and the reverence for the natural world. They viewed themselves as part of a divine landscape, where even the blade possessed a soul.

IV. A Dialogue of Chivalry: East and West

Every civilization develops a class that embodies its highest ideals. Comparing the Western Knight (Chivalry) with the Japanese Samurai (Bushido) reveals the distinct virtues of each culture.

While Western Chivalry flourished under Christian ethics—emphasizing gallantry, the protection of the marginalized, and external social conduct—Bushido leaned toward the introspective. It was a quest for “internal integrity.”

Consider the ritual of Seppuku. While difficult to reconcile with modern sensibilities, for the Samurai, it was a solemn final rite—a way to “unseal the belly” where the soul was believed to reside, proving one’s innocence and sincerity beyond doubt. Each culture, in its own context, sought a way to defend honor at the highest cost.

V. The Modern Legacy: Warriors Without Swords

Though the Samurai class was formally abolished in the late 19th century as Japan modernized, their DNA remains the invisible architecture of Japanese society today.

It lives on in the meticulous devotion of the artisan (Monozukuri), the anticipatory grace of Japanese hospitality (Omotenashi), and the remarkable social order maintained even in times of crisis. These are the modern echoes of a class that viewed life as a continuous “discipline.”

Seeking the Soul of the Samurai

To truly engage with this legacy during your stay, we invite you to look beyond the museums:

- The Art of the Blade: View a Masterpiece sword not as a weapon, but as a “sculpture in steel,” observing the Jihada (grain) created by thousands of folds.

- The Silence of Private Temples: Experience Zen meditation in the very spaces where Shoguns once sought clarity amidst the pressures of statecraft.

- The Aesthetic of Restraint: Observe the disciplined movements of Noh theater—an art form protected and practiced by the Samurai—where a single tilt of a mask conveys a world of emotion.

The Samurai is not a relic of the past. It is a profound answer to a timeless question: How does one live with nobility, integrity, and beauty in an uncertain world?