Days blurred into one another as I chased deadlines, constantly immersed in numbers and schedules. Somewhere along the way, I realized a quiet part of myself had gone dry. Working as a consultant in London, I had grown so accustomed to moving fast that I’d lost touch with something less tangible—but deeply vital.

Then one afternoon, a Japanese colleague I’d been working with said something in passing that stuck with me. “When I’m exhausted, I go to Okinawa,” she said. “The ocean breeze unknots your heart.”

Those words wouldn’t leave me, and when summer arrived, I took a leap and flew to Okinawa.

Okinawa lies in the far southwest of Japan—a subtropical archipelago of over 160 islands. As I stepped out of Naha Airport, the air hit me like a warm sea-breeze infused with the scent of deep greenery. My first stop was Kokusai-dori, the main street in downtown Naha.

It had once risen from postwar ruins to become a bustling hub, and even now, it pulsed with color and energy. Rows of lively shops displayed everything from “shisa” lion-dog statues to “bingata” textiles—traditional Okinawan dye patterns in vivid hues. I was immersed in a different rhythm of life.

Around lunchtime, I wandered into a narrow alley and found an old-fashioned eatery with wooden sliding doors. As I stepped inside, the soft chime of a wind bell greeted me. Handwritten menus lined the walls, and the tables were worn smooth from years of use. I ordered goya champuru, a local stir-fry of bitter melon, egg, tofu, and pork. It was my first time tasting it, yet something about it felt deeply nostalgic—familiar, almost.

“First time trying that?” a gentle voice asked. I turned to see a woman with sun-kissed skin and short, slightly copper-tinted hair, probably around my age. Her calm smile and quiet confidence made me feel at ease immediately.

Her name was Misaki. Born and raised in Naha, she now ran a café with her family and surfed on weekends. There was something steady and strong in her gaze, and we found ourselves talking long after we finished eating.

“Okinawan summers are hot,” she said with a laugh, “but they wash your heart clean.”

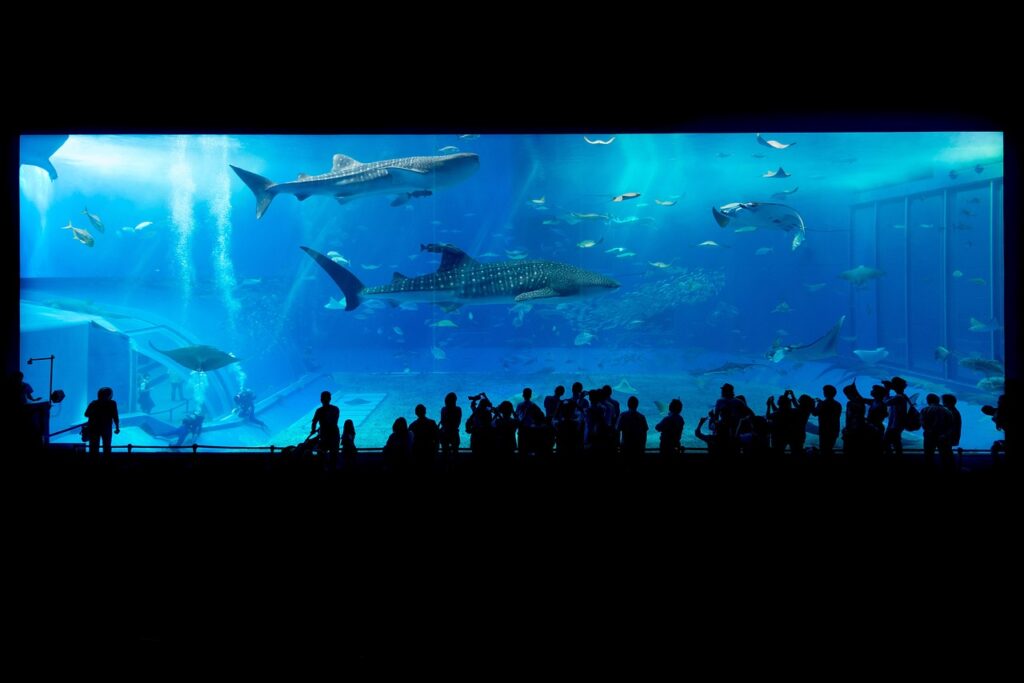

The next day, moved by her words, I headed north. The bus traced the coastline, where the line between sky and sea dissolved into a seamless expanse of emerald blue. My destination was the Churaumi Aquarium, perched on a hill overlooking the ocean in Okinawa’s northwest. It’s famous for its massive tanks, home to graceful manta rays and whale sharks drifting through deep blue waters.

As I stood before the cool glass, I was struck by how different the tempo of life was here. Slow, measured, and deeply alive. Nearby, a young mother held her child close, both of them entranced by the movements of a shark gliding past. Something about that quiet moment—life nurturing life—moved me.

On the way back, I stopped at a roadside stand and bought a sata andagi—a deep-fried Okinawan doughnut. Crisp on the outside, warm and fluffy inside, with a hint of brown sugar that melted on the tongue. As I walked, looking up at the sky, I saw clouds billowing like slow-moving ships on a pale canvas.

Further south, I visited Gyokusendo, a limestone cave formed over hundreds of thousands of years. Cool, otherworldly air greeted me as I stepped inside. Stalactites hung from the ceiling, bathed in blue light, while water whispered through the cavern in a timeless rhythm. Nature’s silent craftsmanship left me speechless. It wasn’t something human hands could ever hope to create. And slowly, I began to understand what Misaki had meant—that feeling of something deep inside being rinsed clean.

For the final chapter of my journey, I visited Shurijo, the former royal palace of the Ryukyu Kingdom. It sits on a hill to the east of Naha and was first built in the 15th century. The architecture blends native Okinawan style with Chinese and Japanese influences, resulting in something entirely unique. The castle has burned down multiple times and has always been rebuilt. It is more than a historical site—it’s a symbol of quiet resilience, of pride, of the will to rebuild again and again, no matter what is lost.

From the castle’s high walls, I looked out over Naha city. The breeze played across my skin, and a thought came quietly: Maybe I hadn’t come here to escape. Maybe I had come to recover something I’d forgotten.

I returned to Naha and visited Misaki’s café. She greeted me with the same warm smile. The space was airy and full of light, with hibiscus flowers arranged near the windows.

“So,” she asked, “how was your Okinawan summer?”

“It felt like a journey back to myself,” I replied.

Misaki nodded gently. “That’s what travel is, isn’t it? A time to meet the parts of yourself you’d forgotten.”

On the plane home, I opened my notebook. The version of me who had once longed for something she couldn’t name had been replaced. I hadn’t just visited Okinawa—I had found something there. The summer, like a breeze or a soft light, had reached into the quiet corners of my heart.

Something New Travel